Quick reactions to some results of the Independent Sector survey with Edelman, in five short answers to one question.

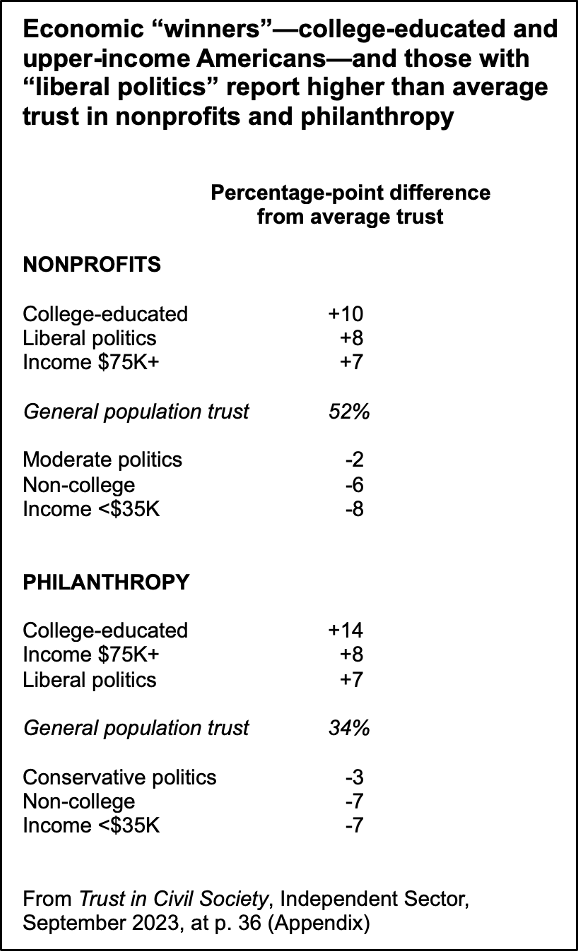

As shown below, the just-released Independent Sector survey of trust in nonprofits and philanthropy, conducted in partnership with Edelman Data & Intelligence, finds that what it calls economic ‘winners’—college-educated and upper-income Americans—report higher than average trust in both nonprofits and philanthropy than non-college-educated and lower-income Americans. Those with “liberal politics” report higher trust in nonprofits than those with “moderate politics” and higher trust in philanthropy than those with “conservative politics.”

Why might all this be, and what should we make of it, if anything?

***

Jeffrey Cain: When companies like Walmart want to create astroturf campaigns to manipulate public opinion in their favor, they turn to the public-relations firm Edelman. When Big Tobacco wanted to sell the public on the health benefits of smoking cigarettes even as its internal research said otherwise, it turned to Edelman.

Private prison companies, Russian oil oligarchs, human-rights violators: if you’re doing something bad but you want the public to think you’re doing something good, Edelman is the go-to PR firm. That’s why after the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, Saudi Arabia naturally relied on Edelman to improve the royal kingdom’s global image.

Now comes the partnership between the special-interest group Independent Sector and Edelman with its latest “research,” with the non-ironic title Trust in Civil Society. The report finds that wealthier and well-educated Americans like the current system of tax-incentivized charitable giving more than poor and uneducated Americans. Successful people, in other words, prefer a system that rewards their success with even greater success.

Now the only thing left to do is to convince—“educate”—the people at the bottom that the current system is in their best interest, even if it mainly benefits the people at the top. And to help make the worse appear the better cause, the Independent Sector could not have found a better partner in Edelman.

Kristen Eastlick: For at least the last two decades, to varying degrees, nonprofits and philanthropies have become increasingly politicized—taking increasingly radical policy, and sometimes openly partisan, stances. They have alienated those with conservative and even moderate views. When these institutions telegraph that the lived experiences and opinions of conservatives and moderates are “wrong,” they can’t expect to be rewarded with their trust.

Michael E. Hartmann: Establishment philanthropy and those policy-oriented nonprofits it funds are overwhelmingly liberal and progressive. I guess I’d trust them more, too, were I a well-credentialed elite with a lot of money and frequent-flyer miles. To me, it seems the most-helpful question to ask in the wake of survey results like these from Independent Sector and Edelman—if it’s okay under TGR rules for my A to pretty much just be another Q—is: will policymakers listen to those less-credentialed, not rich, and more conservative who do not trust tax-incentivized Big Philanthropy so much, maybe seeking to learn from them about the sources of their mistrust, and then contemplate appropriate policy reactions afterwards?

Leslie Lenkowsky: All the latest Independent Sector and Edelman survey tells us is what we have long known: that better-educated, higher-income people have more trust in all sorts of social institutions than less-educated and lower-income people do. And why not? The “economic ‘winners,” as the survey unselfconsciously calls these people, are generally more familiar with them, reap the most benefits from them, and provide more support to them. And it almost goes without saying that this group’s politics are more liberal as well. So what?

The survey says nothing about the involvement of less-educated and lower-income people—the “economic losers,” perhaps?—with society’s institutions, including nonprofits and philanthropy; to put it mildly, conservatives and populists have not shied away from public life in recent years, regardless of how much they trusted its institutions. Indeed, is it possible that less trust might also spur more engagement, as school-board members, for example, have lately found out?

Daniel P. Schmidt: In 2014, Martin Gurri, a geopolitical analyst and expert on new media and information who worked as an analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency, published The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium. In the book, Gurri proposes that current structures of authority are a legacy of the industrial age. These institutions, he concludes, are “without exception, top-down, specialized, prone to pseudo-scientific rituals and jargon.” Outsiders are dismissed out of hand.

Since the early 20th Century, this industrial model of the exercise of power and money was taken for granted—including at the largest nonprofits and philanthropies, peopled by experts at the top of their game.The Independent Sector-Edelman research reveals a gap—increasingly perceived by an increasingly elite-skeptical public—between 1.) the claims made by donors and the institutional recipients of their largesse, and 2.) their actual performance. It shows a peeling away of, as Gurri puts it, “the mystique of the expert at the top of his game.”