This time, however qualified, in Mehrsa Baradaran’s new progressive critique of neoliberalism.

Mehrsa Baradaran’s new The Quiet Coup: Neoliberalism and the Looting of America joins many other histories in citing “the Powell memo” as an important part of their narratives. In the case of The Quiet Coup, the Powell memo helps tell, as Baradaran introduces the book, “the story of how an ideology called neoliberalism infected our politics, creating a complex and impenetrable network of laws and regulations that has created a system which is inherently unfair.” To the large extent that it’s based on a belief in markets as the best way to allocate resources, promote growth, and secure liberty, neoliberalism is associated with free-market conservatism.

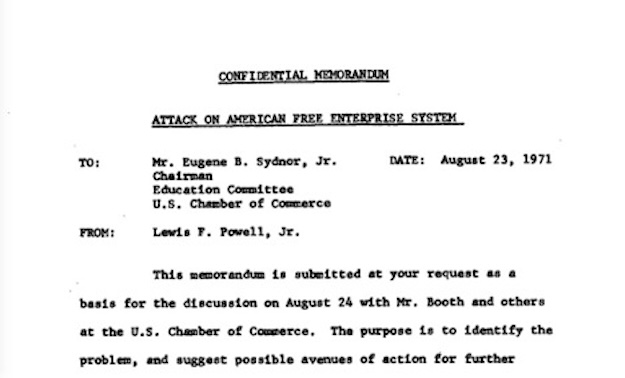

Written in 1971 by corporate lawyer and soon-to-be-Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, the memo advised the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to undertake activities to better and more staunchly defend capitalism and the free-enterprise system against the then-increasing number and severity of attacks on it. The memo has become something of a symbol of the conservative movement, though perhaps more to its progressive critics than its putative members.

“The seven-page memo struck a reactionary tone akin to” Milton Friedman’s, “but it was also full of practical strategies covering a range of issues, making it one of the most significant documents of the neoliberal revolution in America,” according to Baradaran, a professor at the University of California, Irvine School of Law and a visiting professor at Harvard Law School. She is also the author of 2017’s The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap and 2015’s How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation, and the Threat to Democracy.

The Powell memo’s “importance flows not from its originality—many of the ideas within it were already common talking points on the right—but from its clairvoyance,” Baradaran continues. The memo, “circulated in secret and stirring controversy when leaked, predicted the world we live in today. The future was forged by those who fought hardest against progress.”

Significant, predictive, or maybe just inspirational

One might detect some conceptual tension there between the memo being both “one of the most significant documents” of a revolution and it merely being a non-original, albeit clairvoyantly predictive, compilation of already-existing “talking points on the right.”

The role of the memo in supposedly mapping a conservative movement has been overstated by its critics. Baradaran’s book adds a new chapter to this story, albeit qualified.

The memo is cited throughout The Quiet Coup, often placing it on a timeline preceding subsequent activity consistent its content. At one point, it’s mentioned with an ambivalence recognizing the tension between causality or plain antecedence. “It is difficult to know whether the Powell memo caused the surge of corporate activism that followed or was merely reflective of it, but it is clear that what Powell said should happen did happen,” according to Baradaran, for example.

Baradaran quotes another historian, Kim Phillips-Fein, as writing “many who read the memo cited it afterward as inspiration for their political choices.” Baradaran specifically lists subsequent substantial financial support for activities in defense of capitalism and free enterprise from the Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable, Richard Scaife, Joseph Coors, John Olin, and Lynde and Harry Bradley.

As for direct reliance by a philanthropist on the memo for direction, advice, and/or guidance, “Reading the Powell memo led Richard Scaife, the Pittsburgh-based billionaire and supporter of anti-Clinton movements, to begin funding right-wing foundations, the cause to which he would devote the rest of his life and fortune,” Baradaran writes in the book, her work on which was funded by the Hewlett Foundation.

Elsewhere, in 2022’s The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era, University of Cambridge historian Gary Gerstle quotes Olin as writing “The Powell memorandum gives reason for a well organized effort to reestablish the validity and importance of the American free enterprise system,” and says Coors “was also inspired by the Powell memo” in helping create The Heritage Foundation in 1973.

Surely, or not

In 2019, The Giving Review co-editor William A. Schambra—a mentor of mine from when I worked for him on the program staff of The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, which I guess was and still is implementing the memo’s plan—has concisely summarized previous chapters in the “Powell memo”-myth saga, placing it in a little bit of a different, and proper, context.

The late Peter Dobkin Hall, one of the most-prominent and -respected historians of philanthropy had asked Schambra for a copy of the memo, Schambra recalls. “For all its fame as the essential blueprint for conservative public-policy dominance, Hall had been unable to come up with a copy. But he knew me to be a loyal employee of a conservative foundation,” according to Schambra, so

surely, he suggested, I must have a copy of the document—perhaps framed and mounted above my desk, next to my copy of the Constitution.

Except that I didn’t have a copy. Nor, I told him, had I ever read it. I had heard of it by then, but only because persistent rumors had it that my entire career was but a fulfillment of the Memo’s mandate.

Overstated reputation over actual influence. Continuing overstatement, maybe even growing.

Schambra asks, “Why then the persistence of the myth of the Memo?” He offers an answer.

I would say that it provides the left with a far more tidy and convenient explanation for today’s conservative policy activism. A Southern tobacco lawyer (as critics invariably point out) urges the business community to wield its political power ruthlessly against its liberal critics. So today’s conservative presence in American politics must flow directly from the marriage of Southern racism with corporate plutocracy. Perfect fit! But the reality is so much more complicated and interesting.

Avatar and apotheosis, or antithesis

In fact, according to Baradaran in The Quiet Coup, neoliberalism still dominates American public discourse because “it was never about the free market.” While Donald

Trump’s populist nationalism has been interpreted by many as a thorough rejection of neoliberalism, Trump is better seen as an avatar of neoliberalism. Race and racism—or more specifically, fears of an impending global ‘race war’—were the animating forces that led to the rise of neoliberalism in the 1960s and 1970s. Trump was not the antithesis of neoliberalism but rather the apotheosis of neoliberalism’s core logic, stripped of its social niceties.

Since 2016, when Trump surprisingly upended American politics and conservatism, a growing number of nonprofit think tanks, magazines and journals, and activist groups, have arisen to refine or redefine conservatism. They actually would not normally strike one as defenders of an elite neoliberal order; some of them provocatively decry “market fundamentalism,” and they and others urge at least increased attention to the working class.

If and when these groups and their ideas gain further traction, in the right’s intellectual infrastructure and then maybe thus in politics and policymaking, one wonders where progressive critics might find the new equivalent of the Powell memo. It may be needed.