Benda, Gurri, Rufo, and us.

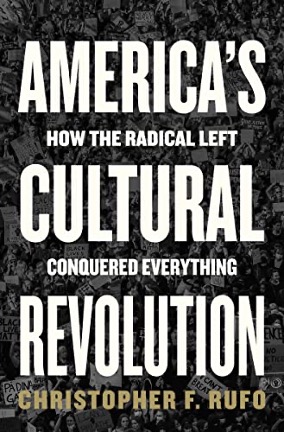

Christopher F. Rufo’s great new book America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything provides a thorough account of the radical left’s assimilation into and subsequent subversion of America’s core educational, social, and cultural institutions.

More important, the book offers a persuasive refutation of the neo-Marxist underpinnings of America’s radical leftist redistributionist and racialist ideology—and offers a strategy designed to create and sustain a counter-revolution against these “commissars of diversity and inclusion.”

“[T]o be successful,” according to Rufo,

the architects of the counter-revolution must develop a new political vocabulary with power to break through the racialist and bureaucratic narratives, tap into the deep reservoir of popular sentiment that will provide the basis for mass support, and design a series of policies that will permanently sever the connection between the critical ideologies and administrative power.

Rufo is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editors of its City Journal, on the publication committee of which the editors nicely allow me to serve. Milwaukee’s Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, on the program staff of which I worked for more than three decades, once supported some of Rufo’s work on the fine documentary film America Lost.

“The principles of the society under counter-revolution are not oriented toward sweeping reversals and absolutes, but toward the protection of the humble values and institutions of the common man: family, faith, work, community, country,” Rufo writes in America’s Cultural Revolution, consistent with his profiles of those patiently pursuing bottom-up civic renewal in America Lost.

Passing political commitment over long-acquired knowledge

As we feared at Bradley and Rufo well understands, the mission of the radical left since the days in the 1960s of the Weather Underground, the Black Panther Party, and the Black Liberation Army have basically become incorporated into the goals and practices of America’s leading educational, business, and social institutions.

To me and my program-staff colleagues, it was and is the result of an intellectual corruption with historical roots, deep enough to reach back many more decades, if not centuries. For example, in 1927, French essayist Julien Benda published his famous—but not as well-known as it should be—La Trahison des Clercs, published in English as The Treason of the Intellectuals in 2017.

That “treason” or “betrayal,” as Benda saw it, came about from the manner in which the intellectuals allowed political commitment to define their understanding of everything in life. Politics became central to their understanding of and work as educators, men of commerce, and creators of culture.

The imperatives of acquiring and disseminating knowledge were devalued. Action took precedence. Accepted political, economic, cultural, and most of all moral values required re-evaluation. Universal norms were cast aside in favor of group identity.

Like Benda, Rufo examines the consequences of such a cultural crisis in society, but recognizes the significant dimensions of the course correction required to restore cultural balance.

A lost claim on legitimacy

Martin Gurri’s 2014 Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium also presages Rufo’s description of the ideological drift of America’s prestige institutions and subsequent sclerosis affecting the leadership class. In Revolt of the Public, Gurri details how the American public has lost faith in the idea of a “common interest” best served by doing good for one’s neighbor, no matter the differences with him or her.

Gurri concludes that elites, as far as the public is concerned, have lost their claim on legitimacy. Generations of the leadership class across the board have ideologically surrendered to the radical left—so much so that current elites, responsible for the protection and transmission of the liberal democratic values upon which our prestige institutions rest, have essentially must abandoned the field.

Rufo’s insightful profiles of Herbert Marcuse, Paulo Freire, Angela Davis, and Derrick Bell, among others, show that they and their fellow radical political philosophers and activists have morally alienated themselves from the public.

In line with implications of the descriptive analyses of Benda almost 100 and Gurri nearly 10 years ago, Rufo’s explicit appeal for launching a populist counter-revolution is in order.

Acting as citizens

There’s a role for philanthropy in the levée en masse in response to Rufo’s call for a counter-revolution, and it too has precedential roots. Perhaps self-servingly, I see in Rufo’s call the same belief of former Bradley Foundation president Michael S. Joyce in of the power of ideas, and of putting them into action. The grantmaking program begun at Bradley under Joyce—pre-“compassionate conservatism,” pre-Tea Party, far pre-MAGA—attempted to apply these beliefs, maybe most prominently in its efforts to initiate and then expand the same parental freedom in education with which Rufo is so familiar, along with work-based welfare reform and other projects.

Joyce constantly referenced the corrosive impact of the Frankfurt School of thought—especially in the post-WWII philosophies of deconstruction and symbolism, which infected our prestige institutions and have caused a concerning precarity on the status of democracy. As started by Joyce, Bradley’s giving strongly reacted to and sought to counteract this impact.

Bradley always wanted to build, or really re-build, from the bottom up. It had and has sought to do so through the same civil-society institutions of family, faith, work, community, and country that Rufo in America’s Cultural Revolution similarly urges be better respected in policy and revitalized in practice.

The aim: to revitalize a healthy civil society in which active citizens could act as citizens, almost always locally, for the common good. Such, too, still in order.