In wake of USC Center on Philanthropy & Public Policy’s must-read report, second of three-part series tracks depressingly increasing evidence of failure.

This is Part 2 of a three-part series. Part 1 is here, and Part 3 is here.

Angelenos awakened last June 4 to this headline in the Los Angeles Times: “Homelessness jumps 12% in L.A. County and 16% in the city; officials ‘stunned.’”

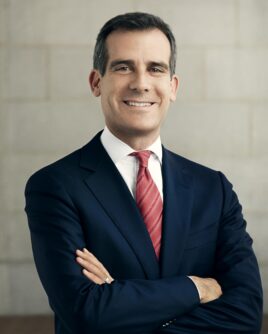

But how could that be? As we described in Part 1 of this series yesterday, the major foundations in Los Angeles had been engaged for years in a cutting-edge, root-cause-driven, social-science based, comprehensive plan to end homelessness. They had united the local business community, major nonprofits, and most government leaders, including Mayor Eric Garcetti, behind a “theory of change” centered on “housing first,” or “permanent supportive housing.”

According to that theory, only one-quarter of LA’s homeless—those chronically homeless from physical or emotional disability—consumed three-quarters of public revenue spent on homelessness. If you could move the chronically homeless directly into housing and provide the social services to keep them there, the theory went, you would actually save money, while driving down the homeless numbers.

So confident in this theory was Los Angeles philanthropy that it moved out of its comfort zone, entering the political arena in order to garner the public funds that would be essential for its realization. In full-on electoral-campaign mode (but no doubt being careful to observe legal limits), the foundations in 2016 secured the passage of Proposition HHH in the city of Los Angeles, which permitted a bond issue of $1.2 billion to build up to 10,000 new units of supportive housing. The foundations followed that success a few months later in Los Angeles County with Measure H, which added $3.5 billion over 10 years to supply a full range of other homeless services, including the support needed to keep the chronically homeless in Proposition HHH’s housing.

As we noted in Part 1, this dramatic story—from the early, painstaking efforts to “build a field” behind a unified theory and a “plan of action” backed by all relevant public and private players, mounting steadily to the triumphant passage of the two ballot measures—is told in Scaling Up: How Philanthropy Helped Unlock $4.7 Billion to Tackle Homelessness in Los Angeles, by James Ferris and Nicholas Williams of the University of Southern California’s Center on Philanthropy & Public Policy.

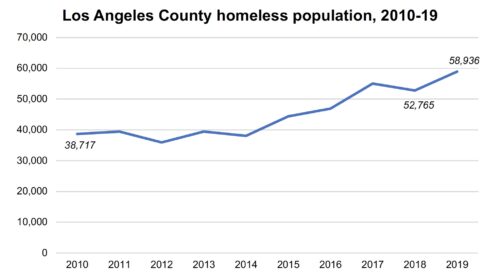

Curiously, when the report was released this past August, no reference whatsoever —not even a qualifying postscript in tiny typeface—was made to the devastating homeless figures that had come out two months earlier. Indeed, the last data point in Scaling Up’s homeless count was two years old by the time the report came out. The timing of the report’s release was, shall we say, not propitious, as Los Angeles was still trying to understand how the count had risen so dramatically and now included about 36,000 individuals in the city and 59,000 countywide, as shown in the chart below.

As the Los Angeles Times story on June 4 put it, the new figures amounted to a “hard reality check for Los Angeles County’s multibillion-dollar hope of ending homelessness.” It “crushed the optimism from last year’s tally, when a modest decrease in homelessness was recorded.” The new numbers “left officials struggling to understand how the tide could have turned so badly in a year when millions of dollars had been spent rolling out two new initiatives to move people into shelters and permanent housing.”

Backers of the philanthropic homelessness collaboration offered various reactions to the new numbers. Without the funds from Measure H, the United Way of Greater Los Angeles argued, things would have been even worse: the increase would have been an estimated 28%. Phil Ansell, the county’s lead official on homelessness, maintained that every day during the previous year, 133 homeless individuals moved into permanent housing—but another 150 became homeless.

The Los Angeles Times itself, long a supporter of the homeless initiatives, conceded in an August editorial that it had been “two years and nine months since voters approved HHH,” and yet “not one unit of housing financed by the measure is open. A single project with 62 units is scheduled to open this November.” Nonetheless, the Times argued, some 8,000 units of new housing were in the pipeline, and they still had faith in the homeless plans.

Mayor Garcetti—once bruited about as a presidential candidate, but now struggling to deal with what he had described to NPR as the “humanitarian crisis of our lives” in his own backyard—echoed the Times’ argument that housing help was on the way. Responding to The New York Times’ Jill Cowan on June 5, Garcetti argued that it was only fair to start measuring results starting right … now: “the first honest year to assess, will be to freeze frame from now to next year.”

Other potential paths

Nonetheless, other advocates for homeless programs are growing impatient, and are exploring other paths forward.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas and Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg, who are co-chairs of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s homeless task force, would ratchet pressure up substantially. They look to New York City’s “right to shelter” law as a model, establishing “the legal right of all people to sleep inside.” At the same time, though, they insist that the right be accompanied by the “obligation for those camping on the streets or on the riverbanks to come inside.” Steinberg adds, “Living on the streets should not be considered a civil right.”

This would, of course, necessitate a move away from permanent supportive housing, in order to fund cheaper housing. Steinberg remains proud, he insists, of his role in establishing a “housing first mentality” in California. And he maintains that he still believes in the concept. “But I’ve also come to see that focusing primarily on permanent housing is insufficient. We simply don’t have the housing stock necessary to address our current crisis, and building it will take too long and cost too much. We need an infusion of short-term shelter and housing options ….”

For many frustrated advocates of homeless policies, there’s no solving the problem without tackling the larger dilemma of expensive housing. Affordable homes and rentals are increasingly rare, according to critics, thanks to California’s restrictive zoning requirements, environmental regulations, and booming economy. Peter Lynn, director of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Agencies (LAHSA), argues that “If we don’t change the fundamentals of housing affordability, this is going to be a very long road.” According to the Los Angeles Times, even Elise Buik, president of the local United Way that spearheaded the drive for HHH and H, believes it’s “necessary to reevaluate [United Way’s] efforts.” She added, “We haven’t focused as much on affordable housing, but we are now.”

Growing doubts

Shifting the discussion to the broader issue of housing bespeaks growing doubt that the philanthropic effort touted in Scaling Up will be, as promised, the definitive solution to homelessness. The shift does, however, open up the possibilities of bipartisan cooperation on efforts to relax regulations that currently make rapid housing construction impossible.

Gov. Newsom, for instance, has signed off on state legislation that will ease the massive regulatory burden of the California Environmental Quality Act on some of the proposed new homeless shelters. The state will also soon consider a measure that would permit higher-density housing near transportation hubs, suspending local zoning ordinances enforcing single-home construction only.

James Broughel and Emily Hamilton of the conservative Mercatus Center agree that “local zoning codes justifiably receive a lot of blame for the state’s high housing costs.” Sifting through the California Code of Regulations, they count some 24,000 restrictions in the housing subsection, employing “395,000 restrictive terms such as ‘shall,’ ‘must,’ and ‘required,’” by far the largest number of any American state. They suggest that clearing out this thicket would present a bipartisan opportunity to make housing more affordable.

Another option under consideration draws on the much-maligned tool of law enforcement, which is some indication of how desperate progressive Los Angeles is becoming in the face of homelessness. For many Angelenos, the problem of homelessness isn’t an abstract number, but a daily assault on their senses as they make their way down their own streets. Homeless encampments by the hundreds have sprouted throughout the county, bringing with them conditions that are breeding rodents and diseases like typhoid fever and typhus.

On the most-immediate level, Los Angeles sanitation workers are actively cleaning up waste dumps near homeless camps and conduct regular “street sweeps” to remove encampments altogether, at least temporarily. A local NBC affiliate runs a regular series entitled “Streets of Shame: Southern California’s Homeless Epidemic,” and periodically highlights some of the most-appalling street conditions. Sanitation workers typically show up shortly thereafter, improving the situation—at least for a few days. Tents and other supplies lost in the street sweeps are often replaced by service providers.

On a more-aggressive level, and even in the face of the steady national and statewide erosion of municipal power to restrict such encampments, some local politicians are nonetheless considering ways to ban sidewalk sleeping in certain zones of the city. Los Angeles City Councilman Mitch O’Farrell hopes to strike a balance between the “needs of people experiencing homelessness and people that we hear from every day who are understandably upset, frustrated, and sometimes traumatized by the conditions they observe in many of our homeless encampments.”

At a City Council meeting in September, Councilman Bob Blumenfield observed that teenagers going to Taft Charter High School in his district “walk into a busy street to avoid encampments lining a highway underpass, sometimes out of fear of someone ‘drugged out with needles in their arm.’” This didn’t go down well with the crowd of homeless advocates at the meeting. They “brought the meeting to a halt, yelling and eventually chanting ‘Shame on you!’”

At the far end of the law-enforcement spectrum is the approach under consideration in Bakersfield, Calif.: jailing people who are homeless for misdemeanor drug offensives like use and possession of heroin and methamphetamine, and even trespassing. In spite of the fact that Kern County is one of the few places in the state that still has relatively affordable housing, the January 2019 homeless count shot up by 108% from the previous year. Kern County District Attorney Cynthia Zimmer estimated that some 80% of the local homeless problem can be explained by drug addiction.

“I think people have been hesitant to to say these kinds of things for a while, even people in law enforcement,” she observed. “Because the transient population, it’s just so sad and it’s so pitiful and you sound like you’re so mean. But to be safe, we’ve got to put some of these people in jail.”

Depressingly, even more doubts

As these alternatives to the approach described in Scaling Up were being considered, a couple of news items in the past month cast further doubt upon its continued viability. The headline of a Los Angeles Times story on October 7 tellingly read “Are many homeless people in L.A. mentally ill? New findings back the public’s perception.”

One of the core tenets of the permanent supportive housing approach, as we’ve seen, is that a low percentage of the chronically homeless suffer from mental illness, substance abuse, health problems or physical disability. Putting them in supportive housing, the theory proposes, will actually save money over the long haul, since they consume a disproportionate percentage of traditional homeless services. The 2019 homeless count conducted by LAHSA seemed to confirm this view: only 29% qualified as having mental illness or a substance-abuse disorder.

But reevaluating the data, the Times found that fully 67% fell into that category. As the article quietly suggested, “the findings lend statistical support to the public’s frequent association of mental illness, physical disabilities, and substance abuse with homelessness.”

UCLA professor Randall Kuhn drew out the conclusion for the housing first approach: “If being on the streets is bad for your health, then ‘housing first’ would be fine if everyone was going to be housed tonight.” But that, of course, hasn’t been possible even with Proposition HHH. “In the meantime,” he continued, “thousands will go unsheltered for years and thousands will enter homelessness directly to the streets. What are we supposed to do to help these people?”

A second bit of news struck even more directly at the faith in housing first. Los Angeles City Controller Ron Galperin released a devastating audit of housing progress backed by Proposition HHH funds. Covering the story, USA Today confirmed that nearly three years after the proposition had been approved, and with all the money out in contracts, not a single unit had actually been opened. Meanwhile, the average cost per unit had risen to $531,373, with some costing over $600,000 each. That actually exceeds the median sale price of a market-rate condominium in L.A., the article noted.

Moreover, the auditor observed, 40% of this hefty price tag was going toward “soft costs,” including non-construction activities like fees, consultants, and financing costs. All of this means that HHH’s promise to build “up to 10,000 new units” will come nowhere near the mark.

“I don’t think anyone can say what Los Angeles has done to create and build housing for the unsheltered has been successful or good enough,” Galperin concluded.

Serious questions about policy-oriented philanthropy

Part 1 of this series concluded with Scaling Up’s optimistic look to the future. Foundations were ready to write “the next chapter in the Los Angeles story—the implementation of Proposition HHH and Measure H,” after their hard work in securing electoral approval of the initiatives in 2016 and 2017.

As we noted, Scaling Up was released in August. But the faith-shaking developments in homelessness described here in Part 2 were already unfolding, beginning with the “stunning” data from the 2019 homeless count—released two months before the publication of Scaling Up.

This certainly represents poor timing. But more important, it raises serious questions about the way major foundations approach their grantmaking today, especially when it leads them to serious involvement in the realm of public policy. Part 3 turns to those questions here.