Thrills on the field, but much more than that.

During the dozen years that he played professional baseball in Milwaukee for the Braves—before the team moved in 1966 to Atlanta, traumatically for us Milwaukeeans—Henry Aaron provided fans and non-fans alike in Milwaukee and Wisconsin countless number of thrill-filled moments. I was one of them.

Former Milwaukee Brewers owner and Baseball Commissioner Emeritus Bud Selig remembered one of those moments while speaking to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in the wake of Aaron’s death last week.

It was September 23,1957. “Hammerin’ Hank” sent a pitch delivered by the St. Louis Cardinals’ Billy Moffett in the bottom of the 11th inning over the centerfield wall into the fir trees. The two-run homer won the game—propelling the Braves to the World Series, where they then triumphed in seven games over the New York Yankees. The Braves beat the Yankees.

(Just to underscore: Milwaukee beat New York.)

“I remember that home run so well he hit off of Billy Moffett,” according to Selig, Aaron’s close friend for more than 60 years who skipped an accounting class at the University of Wisconsin to be at Milwaukee County Stadium that night. “It was one of my greatest thrills.”

So too mine. Eight years old, I was in bed, transistor radio in hand, anxiously anticipating a Braves victory. Aaron delivered. Like Selig, I jumped for joy.

Dedicating himself to giving every bit of himself

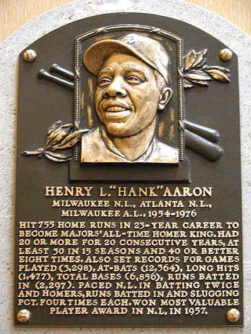

Born and raised in Mobile, Ala., Aaron’s extraordinary skills as a player and, as the years went by, his notable achievements on major-league diamonds ended up making him a Hall of Famer and one of Milwaukee’s most-notable citizens, of course.

But much more than that—and you can maybe discount for my parochialism—I think Aaron was actually perfect for the Midwestern industrial city of Milwaukee. Hard-working. Dedicated. Humble. Faith-centered. Always graciously appreciative of those who respected him as a person. And very generous in giving of his time to others.

Aaron really never stopped giving. He dedicated himself to giving every bit of himself to try creating opportunities and open doors for others. His Chasing the Dream Foundation—established by Aaron and his wife Billye in 1994—has recognized and supported young people who, like Aaron in his own life, work hard every day to achieve their aims.

“The greatest thing, I know people that the home runs, ‘oh you hit 755 home runs,’ but the greatest thing that I feel that the contribution I’ve made since I’ve been out of baseball was to helping 755 in my foundation,” Aaron said in 2011. The foundation set an original goal of helping 755 children, to match his career home runs. It met that number and then kept going, helping hundreds more.

Milwaukee’s Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, where I and my two Giving Review co-editors used to work, was able to offer some modest support to the Chasing the Dream Foundation. Bradley also substantially helped with the construction of Miller Park, which secured the continued presence in the city of the Brewers team that Selig brought to Milwaukee in 1970. (Aaron returned to Milwaukee to play for Selig’s Brewers at the end of his career, in 1975 and 1976, when he hit his final, 755th homer.)

With others, Selig fought hard for Miller Park, now called American Family Field. Its home plate plate rests on a spot just beyond what had been County Stadium’s center field.

Where, in ’57, Hammerin’ Hank sent that home-run ball, giving Milwaukee its shot to take on—making real its dream to chase, and beat—the Yankees.