His caution about “pitfalls and paradoxes” in philanthropy seems quite familiar.

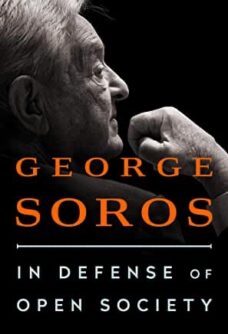

To respectfully mark George Soros’ 90th birthday today, we republish an edited review of his In Defense of Open Society. The review originally appeared here on November 5, 2019.

George Soros presents a collection of his writings related to “open society,” including the mission and work of his Open Society Foundations (OSF), in his new book In Defense of Open Society. Through the essays, Soros assumes the role of a starets. As an elder, secular-spiritual father, he narrates his conceptual framework as it was and is being lived out the in revolutionary moments of these times—if you will, our “Time of Troubles.”

Soros ambitiously exhorts his readers, current and prospective grant recipients, and the men and women of his foundation to go about “defending open societies from their enemies, making governments accountable and fostering a critical mode of thinking,” as he put it in one of the book’s selections, remarks he delivered last year to the World Economic Forum in Davos. “Not only the survival of open society but also survival of our entire civilization is at stake.”

Kim Jung-un, Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, climate change, forced migration, and the degradation of liberal democracies, amongst other plagues of locusts, all challenge our will to survive and weaken our resolve to overcome.

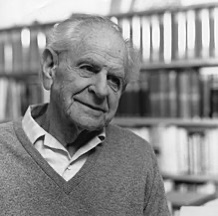

In Defense of Open Society’s final chapter, “My Conceptual Framework,” pays particular homage to philosopher and professor Karl Popper. As a student at the London School of Economics in the late 1950s, Soros was preparing to finish the exams for his degree. In need of a tutor, he turned to the Austrian-born Popper.

In “My Conceptual Framework,” the condensed version of a journal article, Soros testifies that Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies made a profound impression on him. Popper’s attack on “closed” thinking, in particular, underscored for Soros how societies embodying this bad habit of mind promoted intolerance and resulted in the creation of a totalitarian state.

Popper’s concept of change had a deep and lasting impact on Soros. “I used the concept of change,” he writes, “to build models of social systems and reflexively connect them to modes of thinking. I linked organic society with the critical mode of thinking, open society with the critical mode, and closed society with the dogmatic mode.”

Normal rules, confessional moments, and trying to give meaning to ideas

Along with Popper, Soros considers the personal history of his father a major influence on his own education and career. As a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, Tivadar Soros was captured by the Russians, imprisoned in Siberia, escaped only to be caught up in the tumult of the Russian Revolution, and finally returned to Hungary a changed man. George learned from his father the important lesson that in abnormal times, people who follow the normal rules are at risk.

In another of the book’s personal confessional moments, as part of the essay describing his political philosophy, Soros admits to being a “selfish man.” This self-realization convinced him of the necessity to establish a “selfless foundation.”

Greatly influenced by the Austrian philosopher’s theory of scientific method, Soros—the financial wind of 10 years of leading one of New York’s hedge funds at his back—began slowly to organize his thoughts and cautiously engage the world of philanthropy. Cautiously so, lest he fall prey to what he labels its “pitfalls and paradoxes.”

He first went to South Africa to launch a program aimed ultimately at opening the most-closed of societies. Then, on to his native Hungary to establish a $3 million-a-year initiative focused on culture. Since it was still the Soviet times in the ’80s, he wisely included a representative group of intellectuals, professors, and students to surround the all-important dissident contingent. It was during engagements with these groups that he came to know an energetic student later to become the leader of Fidesz, and Prime Minister in 1998, Viktor Orbán.

Early on in these OSF-funded programs, as he describes them, Soros demonstrated his keen sense of those pitfalls and paradoxes. He learned how to give day-to-day meaning to Popper’s ideas of an open society. That meaning’s application included managing grant budgets, establishing efficient local networks, and leveraging and linking national networks to them.

Equally noted and avoided

Indeed, there are some striking similarities between the strategies and operational tactics of OSF in the ’80s and ’90s and some conservative foundations during these years. The same hypocrisies and paradoxes that Soros sees as inimical to philanthropy, for example, were more or less equally noted and avoided by the directors and staff of Milwaukee’s Lynde and Bradley Foundation, where I worked.

Namely, philanthropy should be purposed to benefit others, not be self-serving; it should help encourage individual freedom, not encourage dependence; it should avoid the constant temptations of flattery from applicants; and it should be even more steadfastly aware that program mission is the guiding light of all funding.

Much in the same way as that of conservative foundations such as the Bradley, Olin, Scaife, and Smith Richardson Foundations, moreover, OSF’s work was actually informed by an entrepreneurial spirit. “Breaking the mold” was the goal. Replication, while not possible in every situation, was key to the possibility for achieving successes in advancing public-policy reforms. And, for both the conservative foundations and OSF in the ’80s and ’90s, that which later came to be called “capacity-building” was optimal.

Now, it would seem a stretch to conclude that Soros is a man who shuns recognition; the longing for recognition is cross-ideological, though. One can conclude that Soros does have a common sense, however—which may arise from, among other things, the life experiences of his father or his own in the Budapest of 1944. This sense is surely reflected in the strategy and tactics of Soros at OSF, which have been effective and yielded results that must be acknowledged.